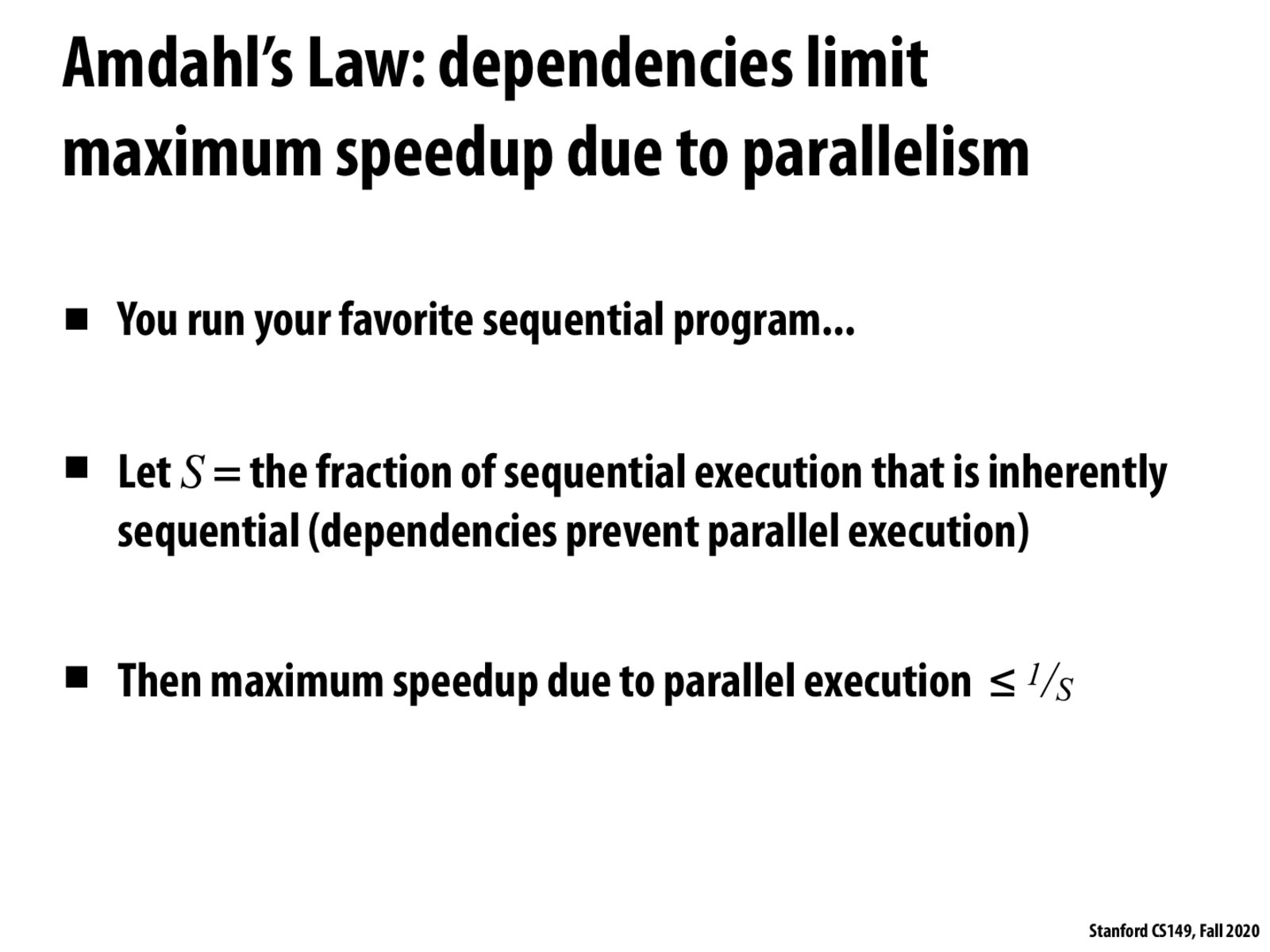

Is there ever a case where it's perfectly 1/S? It seems to me that virtually everywhere there's going to be some amount of overhead, and the more intense the overhead cost the less parallelization actually helps with the speedup.

I think the 1/S is just an ideal bound that is impossible to achieve in reality. Overhead is never likely to be avoided, as there is always some cost incurred by the set-up work, work assignment and communication cost. Also perfectly balanced workload is hard to achieve in most cases.

I agree with @jt, 1/S is just a bound and impossible to achieve. I think it just tells us that even if you have the greatest parallelism and you execute the rest of the program in zero cycle (impossible), you will still have to run S sequentially.

Is there any instances of programs being able to achieve a greater than 1/S speedup? I understand that the theoretical max speedup is 1/S, but maybe due to things like lighter workloads per core or heat throttling during runtime do we observe higher than 1/S performance?

I think Amdahl's law is a simple and effective way to think about upper bounds on speedups due to parallelization. During the first programming assignment, my partner and I were struggling to think of reasons why we couldn't achieve a perfect 8x speedup even after we had divided the work up almost perfectly with 8-way SIMD, and then we independently came to the insight that our program had sequential instructions which were not being parallelized, and therefore the speedup obviously couldn't be 8x. Later on we made the connection to Amdahl's law!

Consider the simple case of SAXPY which requires loading two numbers and writing one number for every operation. If the time needed for reading/writing is M and the actual time needed for sequential computation is N, the time for a sequential program needed is M + N. If we parallelize the computation, the minimum time needed is M, and the upper bound of the speedup is (M + N) / M, which is the inverse of the fraction of the "inherently sequential" part in this program (Amdahl's Law). Just like in the homework, if M is the bottleneck (the memory bandwidth), parallelization won't bring significant improvement of the execution speed.

I just wanted to note that that Amdahl's Law is saying isn't really all that profound. It comes straight from the definition of speedup! Of course it's good to give this idea a name but I don't think we should mystify it too much.

Please log in to leave a comment.

An example for a dependency would be fetching data from an array that lies in memory because this work remains constant between a serial and parallel program.